TANP. Special issue.

Venice Biennale president Paolo Baratta insists that the theme of the current curator Alejandro Aravena – “Reporting from the Front” – follows the throughline set by its predecessors – the search for alternative paths to that of the star architecture that has been tiring everyone since the 2000s. Do you agree with Paolo’s thesis that architecture is taking on greater social responsibility, and that architects are eschewing the superstar complex to pay more attention to public spaces?

Architecture and construction make up the most high-capacity sphere of human activity from the point of view of economics. Second place is taken by the arms industry. Third is space. In terms of cost, all property on the planet is worth more than any other asset. From the point of view of information, architecture and construction involve a very great amount of data. Used correctly, these data might change the world. Architecture follows information and takes the form of a sculptural copy of all events, without exception, taking place in the world, the global information pattern of politics, business, science and art. That is, architecture and the building as an object of design are no longer a matter of politics today. Politics is now to be found in landscape design. If you want to win elections, make the street a more convenient place. Streets and parks cannot be private; these are spaces that belong to everyone. The design of the street has become more socially responsible than the design of buildings. Some countries have made industrial design a part of GDP, and the table has become a matter of politics in such cases. The term “public space” is losing its former meaning and is being used more and more frequently in the rhetoric of work commissions, by those aiming for victory either at elections or in architectural competitions. Some countries have transformed graphic design into a fashionable industry, and there it is font that has become politics. Until architectural practice becomes a banal business, it has the chance to maintain its reputation as an idea-generating discipline.

Why in general, do you think, the Architectural Biennale is needed today, and how important or conventional do you consider Aravena’s theme to be? What theme would you yourself have suggested, if you were suddenly put in his place?

Charlie Koolhaas (photographer and daughter of architect Rem Koolhaas and artist Madelon Vriesendorp – TANR) described the sensation of arriving in Venice with the word “wobbling”. This has now become a professional term, signifying a trip to the Venice Biennale. It’s a state in which you seem to be wobbling on either land or water, floating in the space of the city. When you add to this state all the Biennale projects, an incomparable sensation arises of the presence of some kind of different physical reality. The Architectural Biennale is the only place that proves architecture still exists. The title given by the curator confirms this thesis. It’s an excellent theme for an architect who battles against physical reality and tries to overcome it. Do I feel this avant garde wave? Yes. Do I believe that physical reality can be changed? No. Architecture is a sculptural cast of a preformed information flow, no more and no less. To a certain point you can tell yourself that you are creating this physical reality, but in the process of realisation you understand that what you are doing is the only possible scenario. As, for example, Riccardo Selvatico managed to do in his day, the Venetian consul who, at the end of the nineteenth century, came up with and realised a long-term urban planning theme for his city. In his approach to urbanistics, he was around 150 years ahead of the rest of the world, but if he hadn’t done this, architects would have nowhere to meet.

How do you regard your park project today that you made for the 2008 Biennale? It’s disputed in architectural circles as to whether it would have been better to present the design for the Perm Museum building, with which you won the international competition.

The Project for an international cultural centre on the grounds of the Central House of Artists (TsDKh) was ideally suited for this year’s Biennale: it comprises manifestations of the very same principles. First of all, this project creates public movement and is a public manifesto. Secondly, the project proposes a park with themed pavilions rather than an elite residence, as designed by Norman Foster on the site of the Tretyakovka building. You might say that we were ahead of our time then: this was 2008, back when even the reconstruction of Gorky Park, Sokolniki or the other parks wasn’t yet on the cards. Finally, this project resolves social conflict, which was also something off the agenda at the time. There’s much talk today about the clearing away of the territories around Metro stations, and public space in the city is becoming a part of the project for state security. The same is true for architecture. If we don’t do this, as Aravena says in one of his interviews, “the city will be governed by anger”. And that’s what it was about, the project we displayed at the Biennale in 2008, with the support of Vasily Bychkov, Irina Korobyina, and at the invitation of Aaron Betsky. We produced a series of posters and books. The book was initially to have been entitled Anti-Foster, but after deliberation and many arguments I gave in on this score, and we named the book Pro-Foster as a sign of respect to a great architect. There still exist special editions with an AntiFoster sticker as a more accurate name, better corresponding to the social conflict. As for the Perm Museum, despite winning the international competition, I consider it senseless to support the territory’s former governor, who proved incapable of carrying out his duties. Better to be found beyond the event horizon.

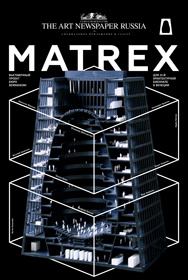

Let’s talk about the MATREX. In a GQ interview, you said that architecture needs irony, without which it would all be for nothing. Is MATREX an ironic project?

As a joke, architecture is too expensive. The meaning of the MATREX building is not hidden, and it is fairly direct: the matryoshka doll as a symbol of art and science, placed within a pyramid as a symbol of business and power. This is a metaphor for soul and body. What jokes could there be here? Don’t you like matryoshki? And why this form in particular? As I understand it, in one way or another, the project was reborn over the course of a decade or so: first the matryoskha travelled around town simply as “architectural mass media”, covered by a screen, and then it was suggested to build it in Japan, and, finally, the project materialised in Skolkovo, where the matryoshka became an empty void. The matryoshka attracted me with its unique combination of complex geometry, minimalistic form, iconic nature and hidden inner content. Virtually an ideal architectural body. But architecture needs more than a body. It needs internal content, a soul. Architecture isn’t walls and isn’t materials, it’s what these walls form. In essence, this is also a void.

Do you recall the classification of postmodernist buildings made by the American architect Robert Venturi? In his opinion, they all in one way or another are either “ducks”, or “decorated sheds”. In scale, the matryoshka resembles a vast popup sculpture. How would you respond if I were to accuse you of having built a “duck building”?

The matryoshka is sufficiently abstract in form that, were you to strip away the decor, it would become something like a cube for instance, a pure geometrical body. If the surface envelope were not too distracting, it could keep this abstractness and turn the matryoshka into an architectural form. But the form of the matryoshka lies on the boundary between an object as plaything and an architectural superform. If something were not done just right, the matryoshka would inevitably transform from an architectural super form into a popup sculpture. Your Hypercube at Skolkovo became a manifesto of how a building might look in the age of new media: it’s covered in screens, capable of broadcasting information non-stop. The MATREX also corresponds to this idea in a nominal way, and the building’s motto is “architecture follows information”. What does this mean? Ultimately, the pyramid itself is a matryoshka. The form of the pyramid, which, as it were, enshrouds and aims to repeat the flowing lines of the matryoshka, is itself of matryoshka form, simply minimalised geometrically. We carried out an identical experiment with our Arch object in the well-known landscape park in the village of Nikola-Lenivets, made for the Arkhstoyanie festival in 2012, where the classical semicircle of the triumphal arch was geometrically simplified to the most minimalistic degree possible – three points. We ended up with a triangular aperture. When you look at the MATREX, you see a pyramid by day and a matryoshka by night. Optically, these are two shapes of contrasting geometry, but in the language of architecture, the pyramid is a geometric simplification of the form of the matryoshka.

Vasily Tsereteli (executive director of the Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art – TANR) believes that you have built a new landmark, and that iconic architecture is important. How would you personally explain the necessity of building an expensive and super-technical conference hall in these times of economic crisis?

If we are to consider architecture from the point of view of such crises, then construction would not be worthwhile at all. According to Marx, crises occur roughly around every ten years. The design, construction and bringing into exploitation of a unique building takes, on average, around eight years. Each unique building thus has a period of only two years between crises to go into the design process. Apart from that, construction is usually carried out on credit, not on your own funds. At the peak of a crisis, credit rates exceed profit margins, and so developers don’t take loans and banks don’t give them. What then is necessary to make architecture without spending your own resources on it? I have no answer to that as yet.

An important component of the MATREX is the museum spiral. You have already financed a series of museum spaces and a great number of exhibitions. How would you evaluate the state of our contemporary art today? What museum spaces are we still in need of?

There is so little of it that Russian contemporary art of the most recent vintage has not yet taken on any global influence. In my opinion, this is connected with the absence of set aims and weakly institutionalised control. Efforts need to be combined. The MATREX building is an attempt to bring together three things: business, science and art. This functional hybrid has also become such a space.

The editor of the book about the Hypercube states that there is an interesting story behind this building: that there are few who have seen it and remained certain of its existence. The same fate may well await the MATREX. Do you feel a little like an architect of mystification?

Contemporary 3D modelling and visualisations are available of such a level that, in principle, you don’t even need to build any more. All spatial sensations can be experienced with the assistance of the first model of Oculus Rift (virtual reality goggles – TANR). The most up-to-date possibilities of computer modelling programmes scare me a little. Brought to life, the built object looks exactly like it does in 3D. But the MATREX definitively exists. I’ve touched it.

Aravena’s theme for this year is about how architecture around the world might improve people’s living conditions, tackling migration, disasters and so on. Why do you think Aravena chose the MATREX to reveal this theme?

As Matthew McConaughey’s character said in the first episode of True Detective, “the earth is all one ghetto, a giant gutter in outer space. Humanity has to stop reproducing and walk hand in hand into extinction”. The modern world doesn’t want to reproduce anything apart from progeny and whatever can be sold for money. The modern world needs an idea. The idea of the MATREX is a building built for the production of ideas. And where else could such production be built but Skolkovo? My first architectural project – an ideas factory for the BBDO advertising agency with Igor Lutz – was about the same thing. Nothing has changed since then. I build the production of ideas, and that is my idea. I’m sure that this is what humanity needs. We have to produce good ideas and realise them, we have to change the world for the better. Only then will our life have any kind of meaning.