LOFT.

STARTING FROM ZERO.

A bleak snow mist covers Moscow when I meet Boris Bernaskoni this grey January morning. The café is hardly distinguished from outside, located as it is on the ground floor of a typical 16-storey Soviet residential block. However, the atmosphere inside and the aroma of fresh baked bread are a contrast to the building’s façade, where a mess of balcony additions – seemingly added at random – overgrow the pale façade. There is no greenery to mute the greyness, leaving the city in a reduced colour scheme.

After a late working evening the night before, Bernaskoni admits he is a bit tired. ‘We are still producing the final drawings for the interior of the Hypercube building in Skolkovo,’ he says ‘and they are calling from the construction site, asking how to make the details.’

During the two decades that have passed since the Soviet Union imploded, Moscow has seen a mixture of collapse, rapid growth and a gradual stabilization of new market sectors. New layers are added on top of the old ones, and an extensive urban expansion is also currently taking shape. As part of the state’s investment in new growth sectors, the construction of the Skolkovo region has just started. When fully realized, Skolkovo will cover 400 acres of land 12 miles from the very centre of Moscow with an entirely new urban area based around science innovation, education and research.

This development has attracted interest from virtually every international architecture studio of note, and will be a growing construction site for years. The very first building is now in place, the Hypercube in Skolkovo, as yet standing alone like a neon-glimmering deep-sea anemone with its sophisticated optical facades in thevast landscape.

‘This is a building that exists not only in the dimension of space, but also in the dimension of time and communication,’ Bernaskoni explains while ordering oatmeal porridge and a pot of tea. ‘It is transformable, and designed to follow the changes that the area will undergo. That is why it’s called the Hypercube – hyper means it contains this fourth dimension which is not connected only to the design of space, but of time.’

For the moment, the building functions mainly as a public space and a platform for communication. In five years, the district will also contain a university as well as a ‘technopark’, and the Hypercube building will be a generator for new start-up enterprises. When housing districts and other office buildings are also in place, it will be integrated as one part of the university campus area.

The Hypercube also serves as a way to display and package the whole idea of this Russian version of Silicon Valley: the building is a flagship of innovative technological solutions with a very high concentration per square metre. The building is a solitary unit, with autonomous systems for energy and water supply. The indoor temperature is kept stable by special heat convectors, waste is turned into household gas, and solar cells contribute to the energy supply. The front façade is made of a thin optic steel mesh, which turns the whole building into a shifting screen of images, presentations and messages from its users.

While the tea is served, Bernaskoni explains Hypercube as layers of hardware and software. The hardware is the skeleton: an exoskeleton, which is the changeable façade, and the internal skeleton parts. Contemporary facades age within 30 – 40 years, but functions age even faster. The software is the internal structure, designed to allow easy transformations during the building’s lifespan.

Boris Bernaskoni was educated in the mid-1990s, and established his own studio right after graduation. This period, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was a chaotic time in Russia, where the ideological and identity base of the whole of society had to be refined, parallel with urgent financial problems and high unemployment.

In many ways it was a kind of vacuum – a time where one system had failed, but nothing had come to replace it. This total lack of orientation seems to have two possible effects: either you lose your own direction too, or you become completely fearless in the search for solutions since anything is equally possible from this point zero.

At first, Bernaskoni’s studio was called A0 – a wink to the large format of international paper standards, but also to the context in which the office started. ‘Point zero is a good place to start from,’ he says. ‘You can go in any direction. Chaos is perfect for an architect, it means there is a lot to do. Emptiness is perfect for an ascetic – and to be ascetic is perfect for an architect, because you start to think about every detail.’

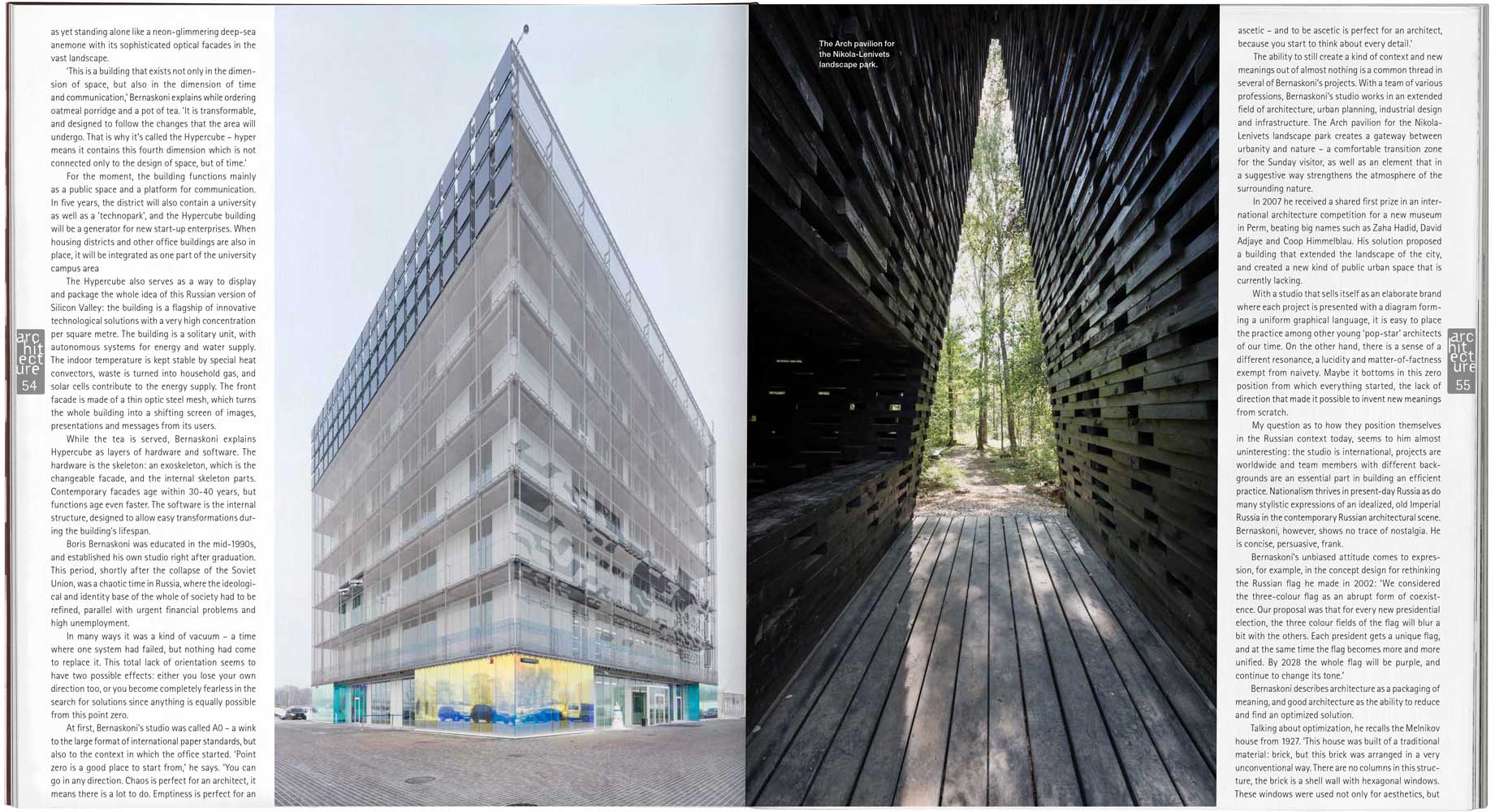

The ability to still create a kind of context and new meanings out of almost nothing is a common thread in several of Bernaskoni’s projects. With a team of various professions, Bernaskoni’s studio works in an extended field of architecture, urban planning, industrial design and infrastructure. The Arch pavilion for the Nikola-Lenivets landscape park creates a gateway between urbanity and nature – a comfortable transition zone for the Sunday visitor, as well as an element that in a suggestive way strengthens the atmosphere of the surrounding nature.

In 2007 he received a shared first prize in an international architecture competition for a new museum in Perm, beating big names such as Zaha Hadid, David Adjaye and Coop Himmelblau. His solution proposed a building that extended the landscape of the city, and created a new kind of public urban space that is currently lacking.

With a studio that sells itself as an elaborate brand where each project is presented with a diagram forming a uniform graphical language, it is easy to place the practice among other young ‘pop-star’ architects of our time. On the other hand, there is a sense of a different resonance, a lucidity and matter-of-factness exempt from naivety. Maybe it bottoms in this zero position from which everything started, the lack of direction that made it possible to invent new meanings from scratch.

My question as to how they position themselves in the Russian context today, seems to him almost uninteresting: the studio is international, projects are worldwide and team members with different backgrounds are an essential part in building an efficient practice. Nationalism thrives in present-day Russia as do many stylistic expressions of an idealized, old Imperial Russia in the contemporary Russian architectural scene. Bernaskoni, however, shows no trace of nostalgia. He is concise, persuasive, frank.

Bernaskoni’s unbiased attitude comes to expression, for example, in the concept design for rethinking the Russian flag he made in 2002: ‘We considered the three-colour flag as an abrupt form of coexistence. Our proposal was that for every new presidential election, the three colour fields of the flag will blur a bit with the others. Each president gets a unique flag, and at the same time the flag becomes more and more unified. By 2028 the whole flag will be purple, and continue to change its tone.’

Bernaskoni describes architecture as a packaging of meaning, and good architecture as the ability to reduce and find an optimized solution. Talking about optimization, he recalls the Melnikov house from 1927. ‘This house was built of a traditional material: brick, but this brick was arranged in a very unconventional way. There are no columns in this structure, the brick is a shell wall with hexagonal windows. These windows were used not only for aesthetics, but as a way to optimize the quantity of the bricks used for the construction. Then he closed 80% of the window openings with waste material from the construction site, but he knew their position so he kept the possibility to open them again in the future.’

Konstantin Melnikov was one of the most influential avant-garde architects in the young Soviet Union. His practice started in 1917, just after the Bolshevik coup when the previous imperial state was drastically overlaid with a new paradigm. That time bears a similarity to the period of Bernaskoni’s development – both periods demanded a strong ability to orient in a chaotic void. The house with the brick walls, besides being a constructivist experiment, was a notable exception from the Bolshevik paradigm. Who else dared to build a private building in central Moscow, at a time when private property was confiscated and communal living was the standard?

But even if Melnikov’s works are easy to read against an ideological backdrop, his private studio with its brick elaboration shows an embryo for what some commentators claim to be the first real ‘new’ style since Modernism – Parametricism. Basically, Parametricism means that the design of a building or object is decided by a complex input of technical data into a computer modelling system which generates the form. By adding information on the movement of the sun, for example, a façade design can be generated that optimizes the daylight conditions in all rooms inside.

The loss of ideological frameworks is not unique for the post-Soviet architecture scene. It is long ago since anyone talked about a certain style or movement, and the architectural development seems driven rather by technical and material innovations. This has shaped an architecture practice which is oriented toward concepts rather than ideas, and the notion of ‘style’ is no longer relevant.

‘The style of contemporary architecture is that there is no style,’ says Bernaskoni. ‘The problem of contemporary architecture, contemporary art, contemporary everything, is that it is this gangnam style – a massive repeat of very little information. Take a building like the Pantheon – two thousand years after its completion it is still operating technically like it was intended, with sophisticated solutions for water drainage and so on. This will not be the case with the Hypercube. At the very best, it will stand there for a hundred years, but I doubt it will even be so long.’