UNCUBE.

A PHILOSOPHICAL MACHINE.

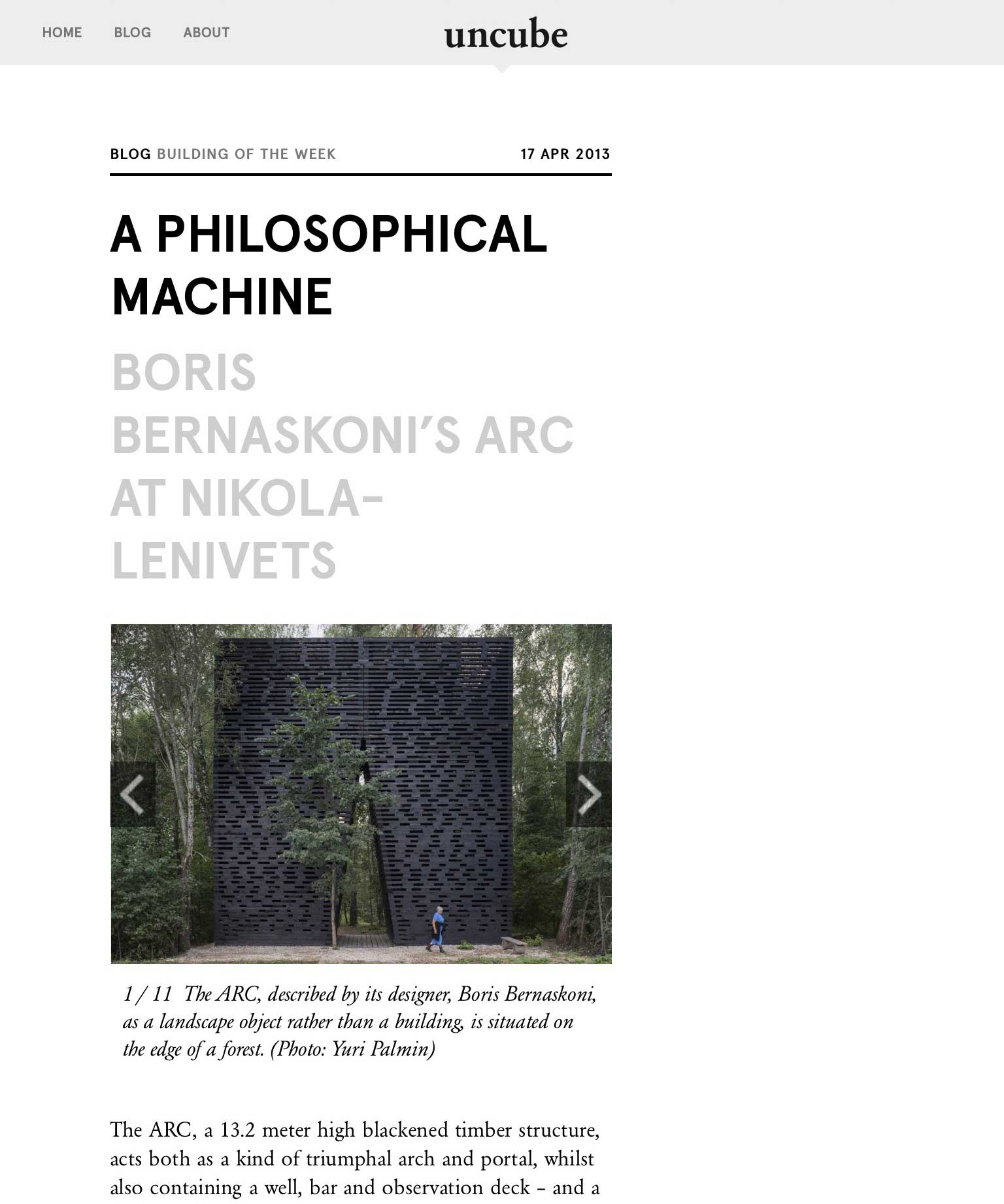

The ARC, a 13.2 meter high blackened timber structure, acts both as a kind of triumphal arch and portal, whilst also containing a well, bar and observation deck – and a single multi-purpose room.

The circumstances around the construction of this hauntingly intelligent architectural offspring of Russian conceptual art tradition are worth relating.

About 20 years ago, the village of Nikola-Lenivets in the Kaluga Region, was a typical dying outpost of Russia’s inhabited realm, with a ruined church, the decaying remnants of an extinct collective farm and just three families surviving on vegetable allotments. This was at the time when Moscow was probably the world’s hot spot of anarchic energy and creative indulgence – for the spectacular collapse of the ‘Evil Empire’ was experienced by many as an Apocalypse and a new Universal Beginning. Artists flew to the West in droves, but there were also those who sought refuge from the looming tsunami of western capitalism in the depths of the Motherland’s frozen backwoods, attempting in remote and autonomous artistic communes to realize fragments of the broken promise of global communism.

Of a number of initiatives of this kind, the “Nikola-Lenivets partnership” is one of the few which has managed to persist and take root – perhaps for the good reason that, compared to the rest, it has always been practically, rather than strictly ideologically, driven.

The place was discovered by Moscow architect Vasily Shchetinin and later given a strong impetus by painter Nikolay Polissky, who’s audacious reinvention of himself as a demiurgic land-artist, succeeded in engaging a posse of desperate unemployed locals in the production of gargantuan-sized open-air installations made from collected natural waste. International attention followed – and not always with benign consequences. By the time I visited Nikola-Lenivets in 2010, the local workforce were busy carving countless numbers of life-sized wooden deer, commissioned by Philippe Starck for a luxury hotel in central Paris.

Yet it wouldn’t be fair to say that everything became corrupted and the initial utopian stance was completely abandoned. For since 2005 Nikola-Lenivets and the surrounding area had become home to an annual land-art/architectural festival “Archstoyanie”, which little by little has attracted almost all remaining reputable figures from Moscow and St. Petersburg, including the artists Alexander Brodsky, Aleksander Konstantinov, Oleg Kulik and Andrei Monastyrski. More remarkably, during all these years Nikola-Lenivets has also been serving as a indispensible testing ground for young architects, artists and experimental musicians.

Among this new breed Boris Bernaskoni is arguably the most eye-catching and inspiring figure, not least because he has been participanting in Russia’s most high profile ongoing international development project, the Skolkovo Innovation Center, a developing high-tech business hub near Moscow, where he has found himself in the company of such architectural moguls as OMA, Herzog & de Meuron, Sejima, Chipperfield and Boeri. Within this challenging and slippery setting his comparatively young age seems to have paradoxically acted as a facilitating factor: his first building: “Hypercube” is already realized, and the second one “Matrix” is being built, whilst the daring proposals of the other architects are still hovering in a mist of bureaucratic negotiations with a high chance of disappearing completely.

Against this background the ARC – Bernaskoni and his team’s contribution to the 2012 Nikola-Lenivets festival – is, in contrast, not intended for exposure to the eyes of powerful clients. Rather, it is a subtle statement of architectural and philosophical insight, addressed first of all at his fellow professionals.

To understand the concept one needs to look beyond the structure’s monumental appearance and see it as an orchestrated sequence of spatial situations, an experience-producing machine. Its fortified city-gate typology is certainly suggestive of various “rites of passage” and perceptual transformations. After the visitor enters under the sharply pointed corbel vault, the seemingly narrow and grimy passage suddenly turns into an archetypal socializing place, generated by a bar on the right. Those who don’t get irrevocably absorbed by the drinks, might notice a smaller opening on the opposite side of the passage, which leads to a spiral staircase. From here you start a dizzying ascent, through a twirl of light beams and glimpses of the outside provided by slits in the outer shell. As you proceed to climb, the slits gradually get wider, heralding arrival on the observation deck, from where a serene airy panorama of the landscape park around can be enjoyed. Here, instead (or on top) of the alcohol, you can taste fresh groundwater from an operational windlass well, which pierces the building from top to bottom, connecting both physically and metaphorically, the heavens with the subterranean world. Before you fully descend again to the “social realm”, down stairs concealed inside the other pier, there is one additional peculiar space to linger in. Called an “artist’s room”, it is actually another, more spacious, well, but this time with you at the bottom, with a bench where one can lie down for a while, staring at the patch of the open sky high above. Like an extended version of Descartes’ oven, or a sensory deprivation chamber, the “artist’s room” provides a clue for rereading the entire structure as an epistemological diagram, an embodied philosophical discourse on three basic conditions of the mind’s relation to reality: resonant – aside from other more recent theories – with canonical Hegelian dialectics of being-in-itself (Ansichsein), being-for-itself (Fürsichsein) and the Absolute.

Whilst there is always a risk of interpreting too literally “mute” spatial poetics as “wordy” intellectual matters (and vice versa), in the case of the Arc these two poles really do seem to merge: in a simultaneously austere, comprehensive, transparent and immaculate way.