PROJECT RUSSIA.

If an iPhone were an edifice.

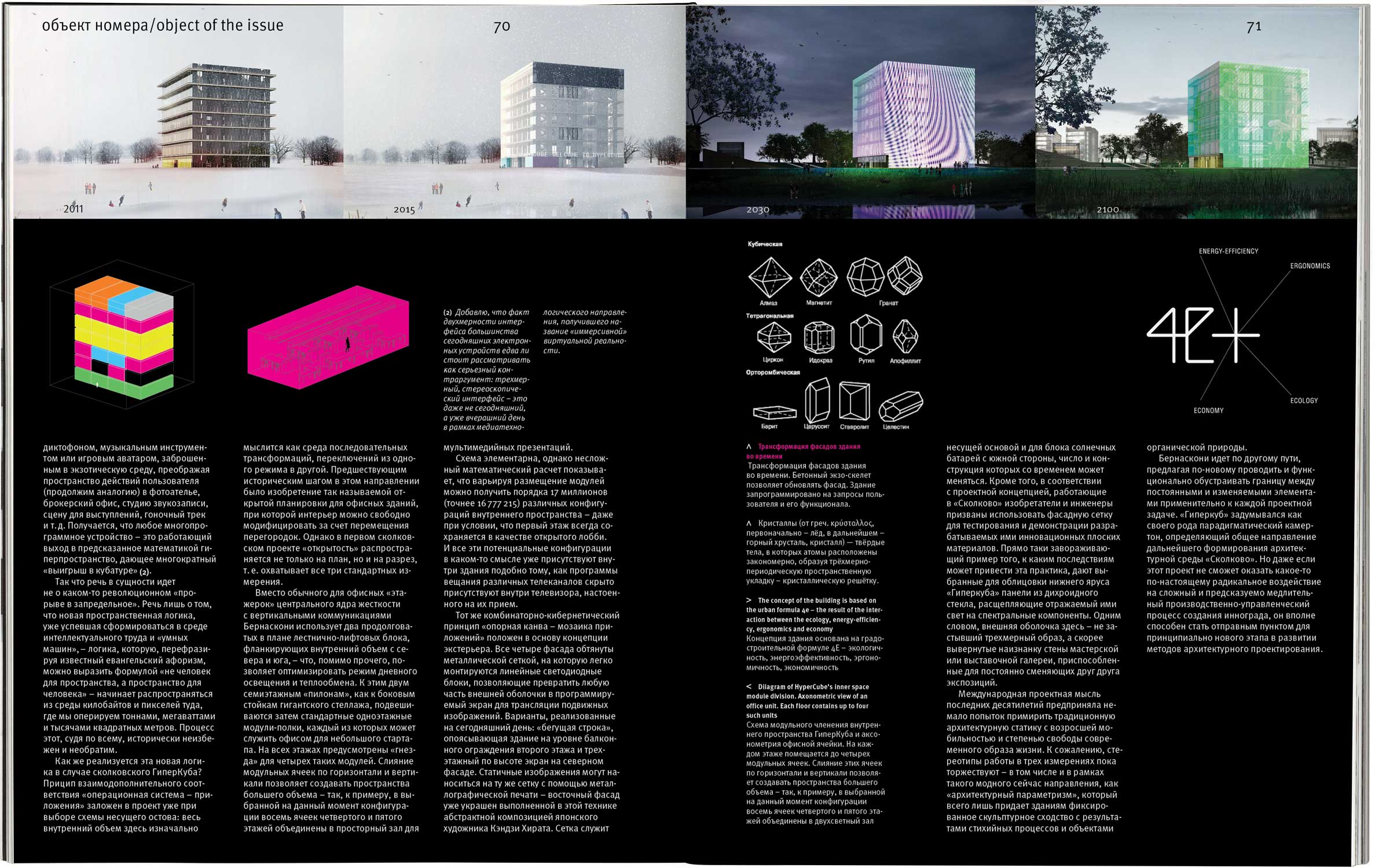

The name of the first structure ever built in the Skolkovo innovation center – the HyperCube – reminds us of the mathematical notion of hyperspace, that is, a space of four or more dimensions. It is unknown whether Boris Bernaskoni who named the building in this intriguing fashion meant the story …And He Built a Crooked House… by Robert Heinlein. But still, the analogy offers itself. The main character of the story is Quintus Teal, an energetic visionary architect who devises the concept of a building in the form of a tesseract – a four-dimensional hypercube – for his client, who, quite coincidentally, is engaged primarily in the oil business. According to Teal’s explanation, backed by mathematical theory, creating the building as a hyperspace portal should provide an eightfold bonus in the cubic volume. If the concept was realized, the total volume of internal rooms would be eight times greater than the external volume of the shell as viewed and calculated from the outside, i.e. from our ordinary, three-dimensional space. The client — quite predictably — refuses to accept the fourth dimension as something real, demonstrating a disappointing inertia of thinking. In the end, a compromise is reached: rather than a tesseract, the building would represent its three-dimensional projection – a four-story vertical object with one-story annexes protruding from it on all four sides.However, on the night before the customer’s first visit, something amazing happens – a minor earthquake collapses the “projection” into a real tesseract with all the features the theory predicted. On the outside, the edifice looks like a nondescript one-story cube, but once on the inside, you find yourself in a system of eight “full-volume” cubes connected to one another in a certain way. This turn of events, unexpected by even the architect himself, turns into not just a series of mind-boggling space adventures, but also into a serious problem: the border between three-dimensional and four-dimensional space turns out to be easy to cross in one direction, but not the other. The house looks like it’s going to tear its first visitors out of the regular world forever. Once the initial amazement gives way to panic, the structure resonates and “collapses” again, disappearing from the earth’s surface and launching its inhabitants into a desert, many miles away from the original location – but this dramatic ending is not so significant in the context of this essay.

Many, like Quintus Teal’s conservative-minded client, tend to believe that practical usage of the fourth dimension, while generally possible, is not possible using the current level of technological development, much like traveling near the speed of light. Bernaskoni tends to follow a different view, consistently moving towards rethinking architecture – in a practical sense – in terms of its interface. Come to think of it, we come into contact with hyperspace on a daily basis. An ordinary television set can serve as an example of hyperspace implementation. But it would be more analogous to look at computer architecture, which is based on a symbiosis of hardware and software, or – at another level – the complementarity of operating system and applications. An application launched from the screen of a tablet or smartphone instantly fills or “occupies” the entire area of user interaction with the device, transforming it into a panel for controlling a photo camera, voice recorder, musical instrument or a game avatar inside an exotic world. To continue the analogy, the user’s activity space is transformed into a photographer’s studio, broker’s office, sound recording studio, performer’s stage, race track, etc. It turns out that any multi-programming gadget is a real, working exit into the hyperspace predicted by mathematics, yielding multiples of “volume gain”.

So, in essence, we are not talking about any revolutionary “breakthrough into the outer limits”. We’re talking about the new space logic, which has been established in the area of intellectual labor and “smart machines” – which, in restating the famous evangelical saying, can be described by the adage “space for humans, not humans for space” – and is beginning to spread from the domain of kilobytes and pixels to where we operate in tons, megawatts and thousands of square meters. Apparently, this process is historically inevitable and irreversible.

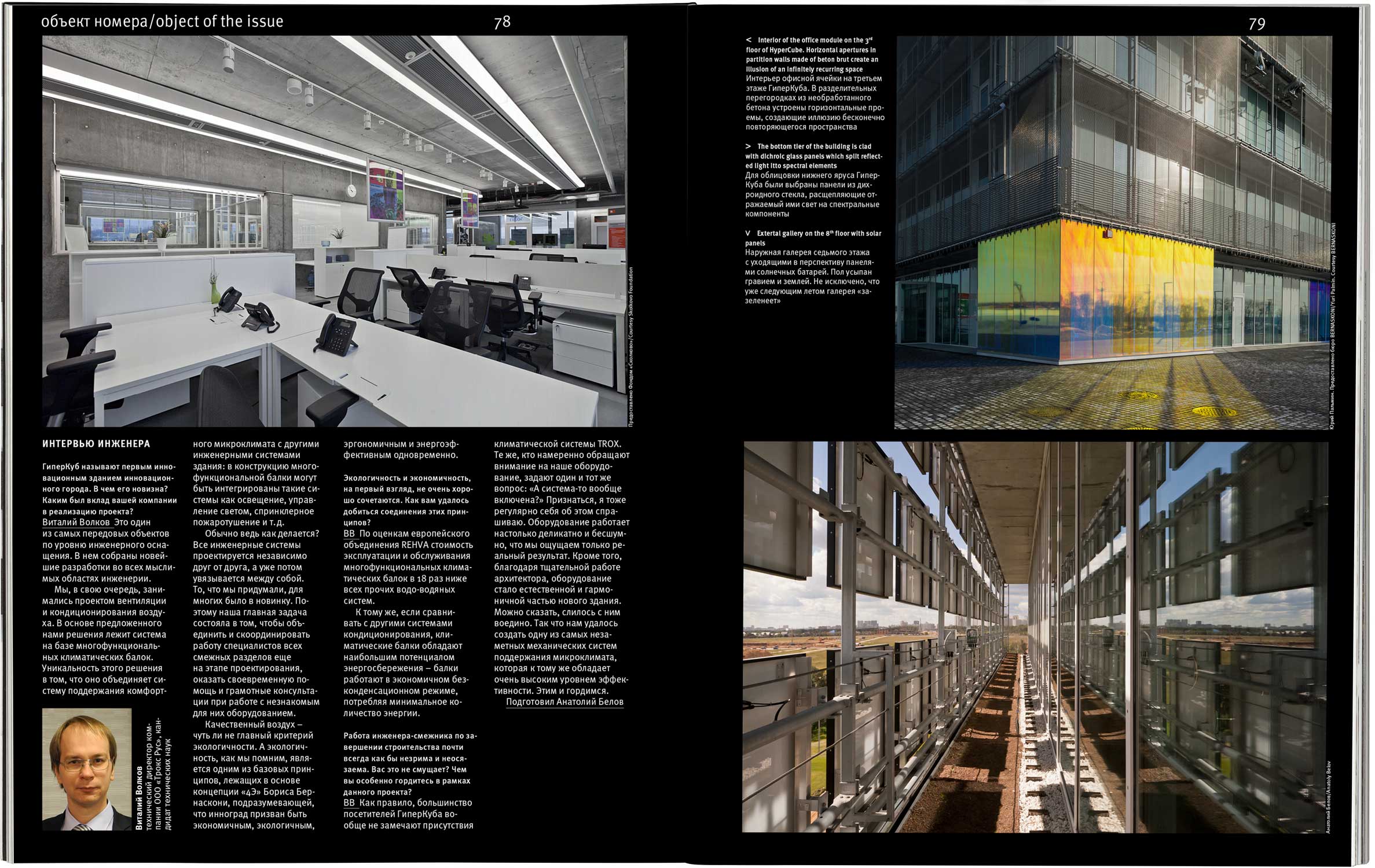

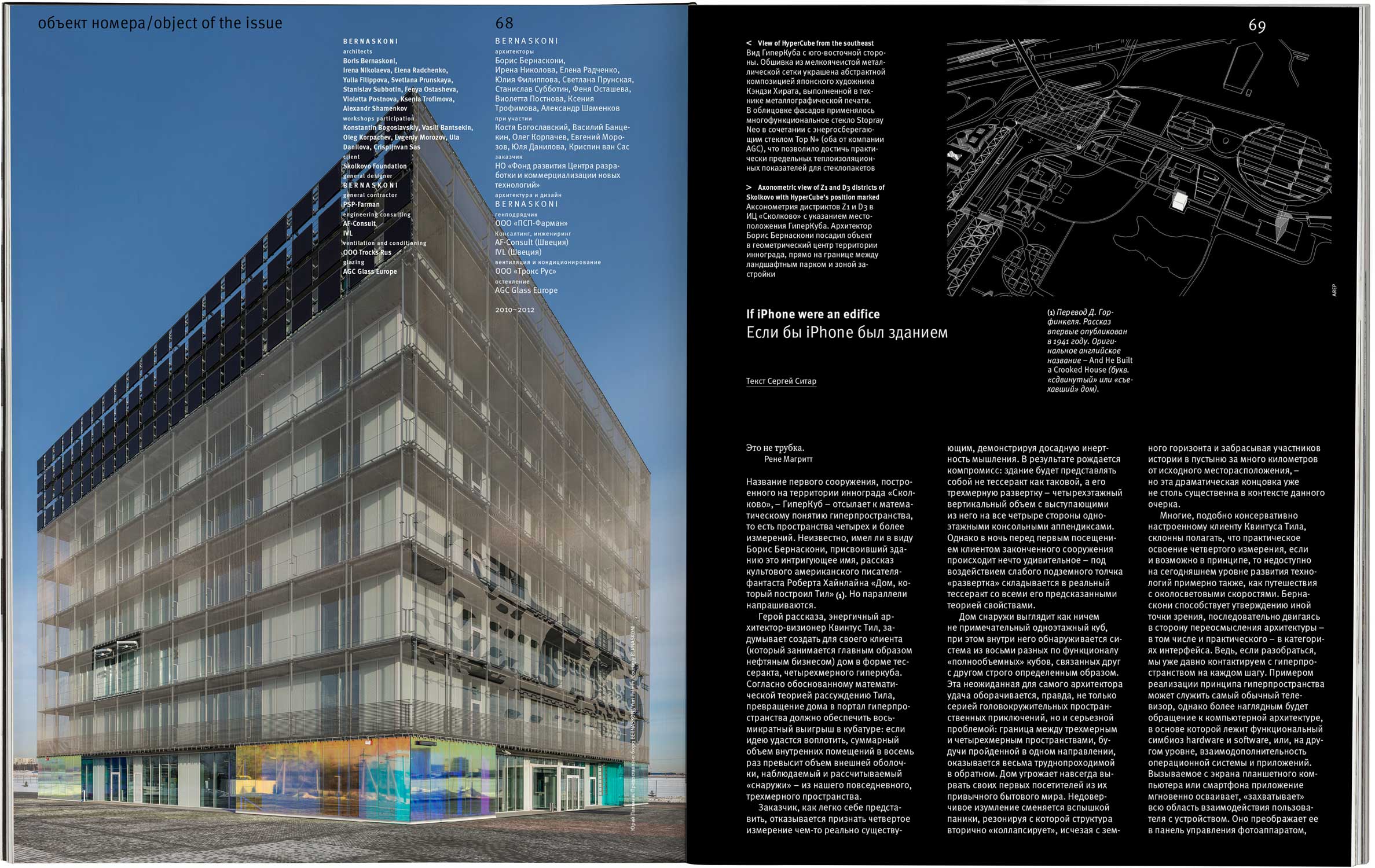

How is this new logic implemented in Skolkovo’s new HyperCube? The principle of mutually complementary combination of “operating system and applications” is included in the design when the building frame is chosen: the entire interior space is thought of as a series of transformations, switching from one mode to another. The last historical development in this area was the invention of so-called “open space planning” for office buildings, where the interior could be freely modified by moving partitions. However, in the first Skolkovo construction project, the “open space” concept spreads beyond just floor plans and also to the building’s cross-section, thus spanning all three standard dimensions. Instead of the central structural core containing vertical communications, which are common for office “stack-frames”, Bernaskoni uses two laterally elongated stairwell-and-elevator blocks flanking the interior on the north and south – which, among other things, helps optimize the building’s daylight illumination and heating requirements. These two pylons span seven floors each and, like the side walls of a giant shelf stand, are connected to standard suspended one-story modules (“shelves”), each of which can be used as an office for a small start-up company. Each floor has four “receptacles” for four such modules. The combination of modular cells in horizontal and vertical planes allows larger spaces to be created – for example, in the current configuration eight cells on the fourth and fifth floors are merged into one spacious hall for multimedia presentations. The concept is not complex, but simple mathematical calculations show that various combinations of modules result in almost 17 million possible combinations of internal space (16,777,215, to be precise) – even if the ground floor is kept as an open lobby at all times. In a way, all these prospective configurations are already present inside the building, just like various TV channel broadcasts are secretly present inside a TV set tuned to receive them.

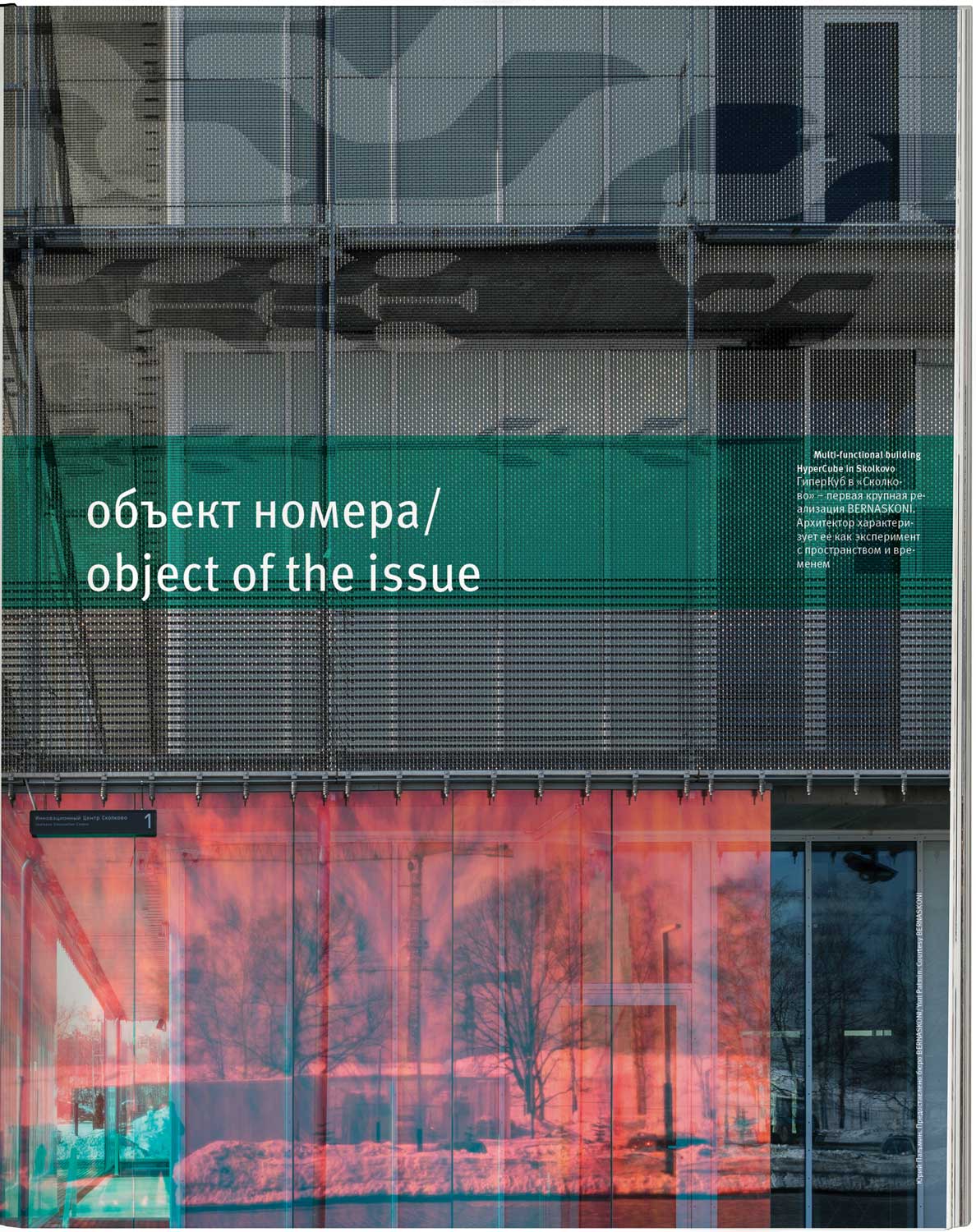

The exterior concept is based on the same combinatory cybernetic principle of a “supporting canvas and an applications grid”. All four facades are covered with a metal mesh for easy installation of LED blocks, which can turn any part of the building exterior into a programmable LED screen to display moving images. The options implemented to date include a “ticker bar” spanning the entire building at the second floor railing level, and a three-story screen at the northern façade. Static images can be installed on the same mesh with metallographic print. The eastern façade, dedicated to the topic of art, is already decorated with an abstract composition by Japanese artist Kenji Hirata. The mesh also carries a block of solar batteries on the southern side of the building, the number and configuration of which can vary with time. In addition, in accordance with the project concept, the inventors and engineers working at Skolkovo are encouraged to use the façade mesh to test and demonstrate innovative flat materials of their own design. Dichroic glass panels provide the most fascinating example of what this practice can lead to. They separate reflected light into its spectral components and have been chosen to line the HyperCube’s bottom level. In other words, the entire outside shell of the building is not a static three-dimensional image, but rather a painter’s studio or an art gallery whose walls have been turned inside out and fashioned to display ever-changing compositions.

The international design concept during the past decades has undertaken a number of attempts to bring traditional static architecture to terms with the increased mobility and freedom of the modern lifestyle. Unfortunately, the stereotypes of working in three dimensions still prevail – including the latest trend of “architectural parametricism”, which merely gives buildings a fixed sculptural similarity with the results of natural processes and objects of an organic nature. Bernaskoni goes in another direction, suggesting a new way to draw the line and functional distinction between the constant and changing elements required for every project task. The HyperCube was conceived as a sort of paradigmatic camertone defining the general development of Skolkovo’s architectural environment in the future. However, even if this design doesn’t yield any radical impact on the complex and predictably slow production and management process in this specific case, it can quite probably become a starting point for an all-new stage in the development of architectural design methods.